![]() Posted by David T. Drummond ⎜ Jun 11, 2018 ⎜ Industry

Posted by David T. Drummond ⎜ Jun 11, 2018 ⎜ Industry

By Wayne Forrest, AuntMinnie.com staff writer.

Major changes are taking place in the intricate network that supplies healthcare providers around the world with molybdenum-99 (Mo-99), a key radioisotope for nuclear medicine studies. The question is, can the nuclear medicine community avoid another devastating shutdown like the one that occurred in 2009?

Back then, providers were left scrambling after a perfect storm left sites without supplies of Mo-99, which cannot be stockpiled due to its extremely short half-life. In the years since the 2009 crisis, nuclear reactor operators, nuclear medicine pharmacies and practitioners, radioisotope generator manufacturers, medical societies, and other stakeholders have banded together to ensure that adequate supplies of Mo-99 and its technetium-99m (Tc-99m) byproduct are consistently available.

“This whole occurrence of 2009 really presented a wake-up call to the industry at large, but I think we have embraced it,” said Sally Schwarz, co-director of the cyclotron facility at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “This has been an extensive and time-consuming process to move this change forward.”

One of the more significant steps to Mo-99 stability was the creation in 2009 of a joint effort between the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA). The goal is to coordinate Mo-99 production and develop ways to ensure that supply meets worldwide demand; the organizations’ members cover the gamut of nuclear medicine enthusiasts and meet every six months in Paris.

The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) are also on hand to advocate for physicians who use radioisotopes in the treatment of their patients.

One of the tenets of the OECD-NEA collaborative is to develop an outage reserve capacity. That means Mo-99 suppliers must have permanent arrangements in place to acquire additional capacity to cover shortfalls when reactors go offline for scheduled or unplanned maintenance.

“On the recommendations of the NEA and OECD, there is a 35% contingency supply,” said Cathy Cutler, PhD, director of the Medical Isotope Research and Production (MIRP) program at the Brookhaven National Laboratory. “If someone goes down, you can call on this 35%. They are basically asking radiators to produce this additional amount.”

The outage reserve capacity is maintained by Mo-99 suppliers paying for extra ports and time on a nuclear reactor. If a supply issue occurs, they then have a position in line to acquire additional Mo-99 to cover the shortfall.

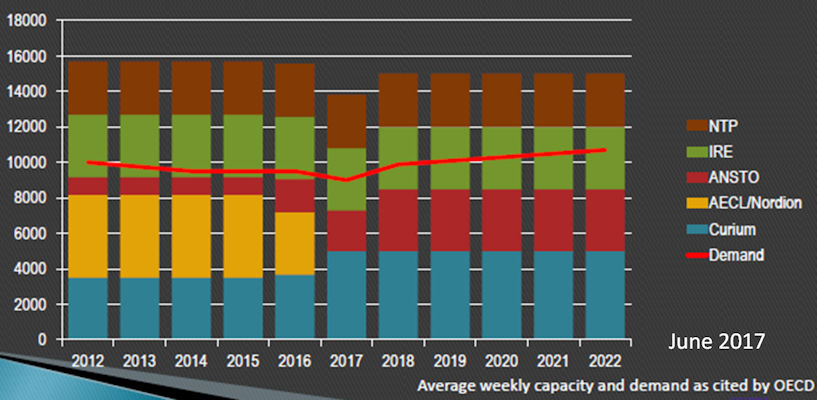

The demand for Mo-99 is expected to grow modestly over the next four years, peaking at approximately 11,500 Ci per week. Interestingly, the anticipated upswing follows a reduced call for Mo-99 in 2017. Currently, the OECD estimates that worldwide demand for Mo-99 is at 9,000 six-day Ci per week. Mature markets account for approximately 84% of the demand, while emerging markets take the remaining 16%. The growth rate in mature markets is expected to remain stable at 0.5% through 2021.

Whatever demands are to come will be handled by fewer Mo-99 suppliers, however. On March 31, the National Research Universal (NRU) nuclear reactor in Chalk River, Ontario, Canada, went offline for the final time after serving North America for decades. Even before its permanent closure, the NRU reactor manufactured little if any Mo-99 since October 2016. In addition, the Osiris reactor in France shut down at the end of 2015. Their departure leaves four Mo-99 manufacturers who now must cover the loss.

See full article here: auntminnie.com

Tags: Latin America Mo-99 North America Radiochemicals Tc-99m